The Life of the Buddha

by Eric Van Horn

Copyright © 2015 Eric K. Van Horn

for free distribution

You may copy, reformat, reprint, republish, and redistribute this work in any medium whatsoever without the author’s permission, provided that: (1) such copies, etc. are made available free of any charge; (2) any translations of this work state that they are derived herefrom; (3) any derivations of this work state that they are derived and differ herefrom; and (4) you include the full text of this license in any copies, translations or derivations of this work. Otherwise, all rights reserved.

Table of Contents

Introduction

So far we have focused on meditation practices that help develop concentration and tranquility. The purpose of this is to train our wild minds and make them instruments of clear seeing and insight. Hopefully that process has already begun for you.

However, this is like learning how to drive. You know how to drive, or you are in the process of learning. But learning how to drive does not tell you where to go or how to get there. That is the purpose of "right view" (or "right understanding"). It is one of the foundations of the Buddha's teaching. "Right view" is the road map, and it shows you the final goal, what some milestones are, and an idea of the different ways to get there. And as with any trip, the exact route you take and what that experience will be like is highly individual.

To be sure, the Introduction to Meditation gives some preliminary idea of where we are headed. As the Buddha said, the best way to practice is a) for our own benefit and welfare now and in the future, and b) for the benefit and welfare of others now and in the future. But that is a little like saying “go north.” Now we want to be more specific.

And one way to understand this landscape is to look at the Buddha's life, and the journey that he took.

Sources

We don’t know exactly when the Buddha was born. There are different timelines, starting from as early as 624 BCE to as late as 400 BCE. The most recent scholarship puts his birth at between 480 BCE and 460 BCE, but there is no consensus on those dates either. Just because it is a round number, I usually use 480 BCE as his birth year. Since he lived 80 years – and that we do know – that would put his death at 400 BCE.

You sometimes read that we know very little about the historical Buddha, and I find that puzzling. We have many thousands of pages of his discourses, over 6,000 in the main four volumes alone, and many of them contain stories about his life. In the Majjhima Nikāya alone there are 4 suttas that give a personal account of the night of his Awakening. Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu notes that “These descriptions are among the earliest extended autobiographical accounts in human history.” [Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu, The Wings to Awakening]

Of course, the purpose of the discourses is not to give a biography of the Buddha, it is to teach the Dharma. But over the centuries many people have rendered the story of the Buddha’s life from this vast literature, and there is a lot of material.

One of the most interesting biographies is relatively recent. It is The Life of the Buddha: According to the Pāli Canon, by the English monk Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli. It is one of the classics of Buddhist literature.

Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli takes information - as the name suggests - mainly from the Pāli canon. It is an amazing achievement, and even if you do not read it, it is worth glancing through to see just how much biographical material is in the canon.

It is possible that we have more biographical material about the historical Buddha than for anyone else from that time period. And in the last 200 years or so there has been an extraordinary amount of archeology in India that has added to our knowledge of Buddhist India. One particularly fascinating read is The Search for the Buddha by Charles Allen. This is not a book about Buddhism. It is a book about how European "Orientalists" found some of the lost sites of the Buddha’s life, and deciphered ancient texts in the same way that the Rosetta Stone provided a gateway into ancient Egypt. We even have cremated remains of the Buddha’s body, so to say that we do not know much about the historical Buddha would be a gross misstatement.

India in the 5th Century BCE

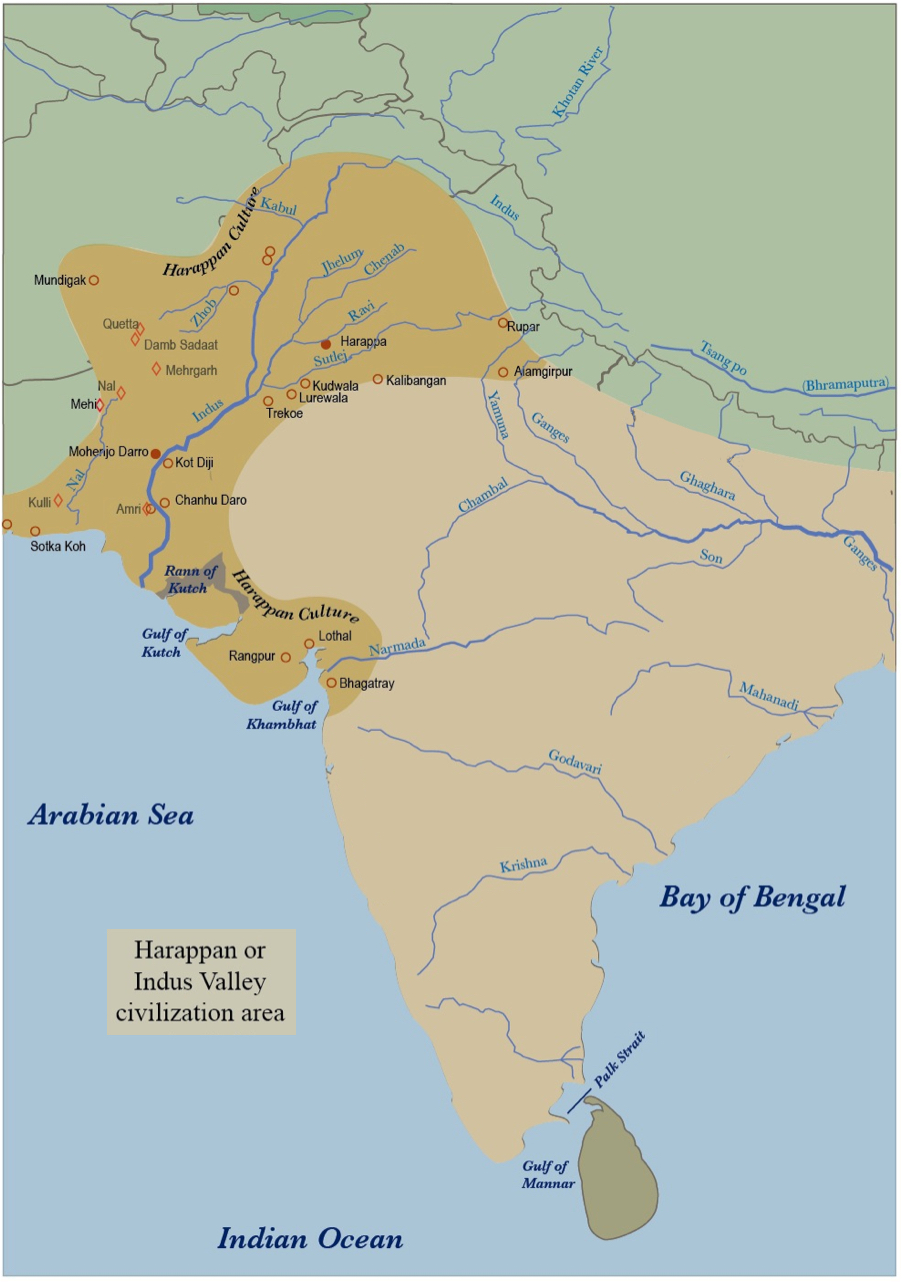

In the 5th century BCE Indian civilization centered in the Ganges River Valley, which is in northeastern India. But that is not where it all started. An earlier civilization grew up in northwestern India in the Indus River Valley. (The word “Indus” is where “India” gets its name.) Relatively recent archeology – circa 1920 – has uncovered a number of these early Indian cities, most notably "Harappa" and "Mohenjo Darro":

Figure:

The Indus River Civilization

Figure:

The Indus River CivilizationThere are some interesting aspects to these early cities. There are no palaces or large houses. This indicates an egalitarian society. There are no temples, which is especially interesting for a country that puts religion at the core of its being. However, small clay objects were found that appear to have pictures of meditators on them, so the practice of meditation may have been known.

Subsequently Aryans came down from the north, and either conquered or simply merged with Harappan culture. The Aryans brought a different culture, with their own Vedic religion, and a class system called the "Varṇas". The Varṇa class system divided all Aryans into three hereditary classes, the "Brāhmaṇas", whose duty it is to maintain the Vedic religious tradition, the "Kṣatriyas", who were the ruling and warrior class, and the "Vaiśyas", who were the agricultural and merchant class. Non-Aryans made up a fourth class, the "Sudras", or servants.

(Note: The Buddha is sometimes criticized for not talking about untouchability. But untouchables did not exist in India until long after the Buddha died.)

Eventually the Brahmins would be the most powerful class, but during the Buddha's time the Kṣatriyas yielded the most power. The Buddha was a Kṣatriyan.

The merging of these two cultures has implications for the India of the Buddha’s time. By his time there were two different religious groups. Vedic religion, which was the precursor to Hinduism, centered on animal sacrifice and complex rituals performed by the Brahmin priests. Vedic religion believed in reincarnation, and that the release from an endless cycle of rebirths could only be achieved through the skillful performance of these rituals.

In contrast to the Brahmins were the "samaṇas", or “recluses”. They did not accept the Vedic religion. They were usually celibate, they lived by begging for alms, and their status in Indian society was by virtue of renunciation, and not membership in a Varṇa. They were religious seekers, who spent their lives in homelessness, roaming around the countryside preaching their various doctrines and sometimes debating with each other. Many of them adopted ascetic practices, some of which were quite severe.

There were key threads that ran through the religious and philosophical thinking in ancient India. These included the concept of Dharma, the concept of karma, and the belief in reincarnation.

- Dharma (Sanskrit, Pāli: Dhamma)

- Karma (Sanskrit, Pāli: Kamma)

- Reincarnation (usually called "rebirth" in Buddhism to distinguish it from the idea that some permanent entity is reborn)

While the word “Dharma” has come to be associated with Buddhism, in ancient India it was a more general term. The idea of Dharma had two aspects to it. The first aspect was an understanding of how things are, of the basic nature of life, or, as Douglas Adams put it, “life, the universe, and everything.”

The second aspect of Dharma is that given a certain understanding of how things are, there is a way to act and behave that is in harmony with that understanding. As Rupert Gethin puts it:

The notion of Dharma in Indian thought thus has both a descriptive and a prescriptive aspect: it is the way things are and the way to act.

- [Rupert Gethin, The Foundations of Buddhism]

The different religious schools of ancient India all had different Dharmas, and this was one feature that distinguished one school from another.

The second common thread was that of karma. The fundamental idea of karma is that each individual has a certain amount of karma from this and previous lifetimes. Whether such a thing as karma exists, and how you accumulated it, was one of the things that differentiated the different schools of Indian thought.

The final thread in ancient Indian thought is the belief in reincarnation. The idea of reincarnation is that when you die, you are reborn into a certain realm depending on your karma. The different realms include the heavenly realms, the human realm, the animal realm, the ghost realm, and the hell realm. Of course some schools did not believe in reincarnation, and some did not believe in karma, but all schools would have had to address those issues because they were so common in Indian thought.

The Buddha grew up in Sakya, which straddles the border between modern day India and Nepal. Sakya was just to the north of the Aryan kingdoms of Kosala and Magadha, which were the two Indian superpowers of the day. Sakya was an early Indian republic, and it paid tribute to Kosala. Sakya was ruled by elected chieftains, and the Buddha's father, Suddhodana, was one of those chieftains. Certainly his father was a wealthy, powerful and influential person by the standards of the day. Tradition later held that the young Buddha-to-be was a prince who was born to a royal family, but this is not entirely accurate. In fact, the democratic, egalitarian ideals of the early Indian republics stood in stark contrast to the heavy-handed monarchies.

This was the world into which the future Buddha was born. It was against this backdrop of Indian society that a woman named Maya gave birth to a baby boy, naming him "Siddhārtha Gautama".

Homeleaving

While there is a great deal of interesting information about Siddhārtha’s birth and early life, our purpose here is to use the Buddha’s journey to Awakening as a way to understand his Dharma, so I will leave that part of his life to another project.

Siddhārtha’s birth mother Maya died shortly after his birth, and he was raised by one of the most important women in Buddhist history, Pajapati. She is usually called "Mahapajapati", “Maha” being an honorific term that means “great” (as in "Maharaja"). She was Maya’s sister, and by all accounts a uniquely giving, loving, and altruistic person.

Siddhārtha’s step-mother would later convince him to start the first order of nuns in the world.

When he was 16 he married the beautiful princess Yasodharā, who also figures prominently in Buddhist history. (She will become the second nun in the world.) But for reasons that are not clear, she does not become pregnant until he is 29 years old. There is some indication that Siddhārtha felt pressured into providing an heir, and resisted. Despite his privileged position, beautiful wife, and loving parents, he was listless:

Bhikkhus, I was delicately nurtured, most delicately nurtured, extremely delicately nurtured. At my father’s residence lotus ponds were made just for my enjoyment: in one of them blue lotuses bloomed, in another red lotuses, and in a third white lotuses. I used no sandalwood unless it came from Kāsi and my headdress, jacket, lower garment, and upper garment were made of cloth from Kāsi. By day and by night a white canopy was held over me so that cold and heat, dust, grass, and dew would not settle on me.

I had three mansions: one for the winter, one for the summer, and one for the rainy season. I spent the four months of the rains in the rainy-season mansion, being entertained by musicians, none of whom were male, and I did not leave the mansion. While in other people’s homes slaves, workers, and servants are given broken rice together with sour gruel for their meals, in my father’s residence they were given choice hill rice, meat, and boiled rice.

Amid such splendor and a delicate life, it occurred to me: ‘An uninstructed worldling, though himself subject to old age, not exempt from old age, feels repelled, humiliated, and disgusted when he sees another who is old, overlooking his own situation. Now I too am subject to old age and am not exempt from old age. Such being the case, if I were to feel repelled, humiliated, and disgusted when seeing another who is old, that would not be proper for me.’ When I reflected thus, my intoxication with youth was completely abandoned. - [AN 3.38]

This is an extremely unusual young man.

H.W. Schumann, in his book The Historical Buddha, suggests that Siddhartha made a deal with his parents that if he provided an heir, he would be allowed to leave and become a samaṇa. This would explain, suggests Schumann, why he left immediately after his son Rahula was born, which is exactly what he did.

This part of the story causes quite a stir in the West, especially among women. The fact that Siddhartha left his wife and baby boy does not sit well with some people.

I don’t know that I can put that angst completely to rest. However, as Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu points out, throughout history men left home to secure the family’s fortune and future. Merchants would be away for years on trading missions. Even into the 19th century men went off on whaling voyages that could take years. Siddhartha was trying to secure the family’s future in a much more transcendent way, one that if successful, would show the way to freedom from the rounds of rebirth for everyone, including his family.

(And while I hate to give away the punch line, the Buddha’s father, step-mother, wife, son and many cousins all eventually became enlightened. Some of my favorite discourses of the Buddha’s and some of his most endearing are teachings that he gave to his little boy Rahula, who was only 7 years old at the time. So ultimately it was a pretty good thing to be related to the Buddha.)

Also, this was in India, where even today the extended family raises the children. The Buddha's family was wealthy and powerful. It is not like Yasodharā was a destitute single mom.

(Later stories said that Yasodharā was fiercely loyal to her husband. When she heard that he was leading the "Holy Life", she started wearing yellow robes and eating only one meal a day. The Buddha's parents freed her from her marriage vows, but she refused to marry anyone else.)

Whatever the situation, I can only say that I am glad he did what he did.

He describes his home-leaving in the Majjhima Nikāya:

…while still young, a black-haired young man endowed with the blessing of youth, in the prime of life, though my mother and father wished otherwise and wept with tearful faces, I shaved off my hair and beard, put on the yellow robe, and went forth from the home life into homelessness. - [MN 26.14]

The Noble Quest

In the first part of the Buddha’s life, he examined his life of wealth, luxury and power, and ultimately considered it futile. No matter what his status in life, he would inevitably grow old, get sick, and die. He wanted to see if there was something better, a higher form of happiness, a greater aspiration than simply self-indulgence.

He traveled down the Ganges River valley to Rajagaha ("raja" – king, "gaha" – home of), the center of the Magadha Empire, and setting off from there he found his first teacher, Āḷāra Kālāma. The Buddha was able to learn Āḷāra Kālāma’s teachings, and eventually he was also able to realize them through “direct knowledge.” What Āḷāra Kālāma taught him was how to enter the "base of nothingness", which is the third immaterial attainment of meditative absorption.

If that last line made your eyes glaze over, let me back track and explain what that means. In the first section of this guide, you learned several concentration and tranquility practices. According to the Buddha’s system of meditative development, this will – perhaps after long and diligent practice – lead to the first meditative absorption, or "jhāna". There are four jhānas. When you have mastered the first four jhānas, one course of practice is to go on to the "immaterial attainments", of which there are five. The third immaterial attainment is the "base of nothingness". I will be describing this process in detail in the section on "right concentration". But for now it is only important to understand that what the Buddha learned from Āḷāra Kālāma, although it was a substantial meditative accomplishment, was not something that led to final Awakening:

Thus Āḷāra Kālāma, my teacher, placed me, his pupil, on an equal footing with himself and awarded me the highest honor. But it occurred to me: ‘This Dhamma does not lead to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation, to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna, but only to reappearance in the base of nothingness.' Not being satisfied with that Dhamma, disappointed with it, I left. - [MN 26.15]

The terseness of that last sentence is quite dramatic. Attaining the "base of nothingness" is a considerable achievement, and Āḷāra Kālāma – as evidenced by his offer to co-teach this Dharma with the Buddha – was aware that he had a star pupil on his hands. Nonetheless the Buddha decided that this was not what he was looking for, and moved on.

His next teacher was Uddaka Rāmaputta. The process was very similar. Uddaka Rāmaputta was able to teach him the next immaterial attainment, the "base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception":

Thus Uddaka Rāmaputta, my companion in the holy life, placed me in the position of a teacher and accorded me the highest honor. But it occurred to me: ‘This Dhamma does not lead to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation, to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna, but only to reappearance in the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception.’ Not being satisfied with that Dhamma, disappointed with it, I left. - [MN 26.16]

So the story repeats. The Buddha masters the next highest attainment, and in so doing earns the respect of his teacher. Still, he is not satisfied.

While it is not stated explicitly here, the states of jhāna, as well as the immaterial states, while they are difficult to master and offer various levels of freedom and satisfaction, are still conditioned states. They have a profound effect on the mind. They lead to greater mindfulness, greater skill, greater virtue, and greater happiness. But ultimately they are still conditioned. The Buddha was looking for something unconditioned. (One of the synonyms for "nirvāṇa" is "the unconditioned".)

Next the Buddha took up ascetic practices. The idea behind ascetic practices is that by torturing the body you free yourself from the rounds of rebirth. Being who he was, the Buddha undertook them with uncommon diligence. He describes in agonizing detail where this led him:

I thought: ‘Suppose I take very little food, a handful each time, whether of bean soup or lentil soup or vetch soup or pea soup.’ So I took very little food, a handful each time, whether of bean soup or lentil soup or vetch soup or pea soup. While I did so, my body reached a state of extreme emaciation. Because of eating so little my limbs became like the jointed segments of vine stems or bamboo stems. Because of eating so little my backside became like a camel’s hoof. Because of eating so little the projections on my spine stood forth like corded beads. Because of eating so little my ribs jutted out as gaunt as the crazy rafters of an old roofless barn. Because of eating so little the gleam of my eyes sank far down in their sockets, looking like the gleam of water that has sunk far down in a deep well. Because of eating so little my scalp shriveled and withered as a green bitter gourd shrivels and withers in the wind and sun. Because of eating so little my belly skin adhered to my backbone; thus if I touched my belly skin I encountered my backbone and if I touched my backbone I encountered my belly skin. Because of eating so little, if I defecated or urinated, I fell over on my face there. Because of eating so little, if I tried to ease my body by rubbing my limbs with my hands, the hair, rotted at its roots, fell from my body as I rubbed. - [MN 36.28]

At this point he was almost dead. If he continued down this path much longer, he was going to die. And while the Buddha was diligent to a fault, he was not stupid. He knew that he had gone as far as it was humanly possible to go with these practices, and they had not led to final liberation:

I thought: ‘Whatever recluses or Brahmins in the past have experienced painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, this is the utmost, there is none beyond this. And whatever recluses and Brahmins in the future will experience painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, this is the utmost, there is none beyond this. And whatever recluses and Brahmins at present experience painful, racking, piercing feelings due to exertion, this is the utmost, there is none beyond this. But by this racking practice of austerities I have not attained any superhuman states, any distinction in knowledge and vision worthy of the noble ones. Could there be another path to enlightenment? - [MN 36.30]

In Buddhism thinking often gets a bad name. But the Buddha thought a lot. He did a lot of analysis, especially now, when he was turning away from any known spiritual path. He started looking for something entirely different, entirely new. At one point, he reasoned thus:

Suppose that I divide my thoughts into two classes. Then I set on one side thoughts of sensual desire, thoughts of ill will, and thoughts of cruelty, and I set on the other side thoughts of renunciation, thoughts of non-ill will, and thoughts of non-cruelty. - [MN 19.2]

It is an extraordinary mind, one that is bringing the process of scientific inquiry to the fundamental problem of the human condition. He is both the scientist and the subject. And despite his desperate physical condition, his thinking is coldly logical.

At one point in this process he remembered a time of great peace and serenity from his childhood, and he reflected on it:

I considered: ‘I recall that when my father the Sakyan was occupied, while I was sitting in the cool shade of a rose-apple tree, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, I entered upon and abided in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought, with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion. Could that be the path to enlightenment?’ Then, following on that memory, came the realization: ‘That is indeed the path to enlightenment.' - [MN 36.31]

This is a crucial moment in the Buddha's quest.

Buddhism is sometimes called “The Middle Way.” That phrase is often used in inappropriate contexts. What it really means is seen here. The Buddha started life rich, famous, and powerful. He had everything that a worldly life had to offer, and he rejected that as being ultimately unsatisfying.

Next he went to the other extreme. He almost killed himself:

Now when people saw me, some said: ‘The recluse Gotama is black.’ Other people said: ‘The recluse Gotama is not black, he is brown.’ Other people said: ‘The recluse Gotama is neither black nor brown, he is golden-skinned.’ So much had the clear, bright color of my skin deteriorated through eating so little. - [MN 36.29]

But now he has rejected both paths as being unsatisfactory. And thus was born "The Middle Way", the path that lies between self-indulgence and self-abuse. He would later say:

Bhikkhus, these two extremes should not be followed by one who has gone forth into homelessness. What two? The pursuit of sensual happiness in sensual pleasures, which is low, vulgar, the way of worldlings, ignoble, unbeneficial; and the pursuit of self-mortification, which is painful, ignoble, unbeneficial. Without veering towards either of these extremes, the Tathāgata has awakened to the middle way, which gives rise to vision, which gives rise to knowledge, which leads to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna. - [SN 56.11]

The key phrase in his analysis is "pleasure born of seclusion". The Buddha would eventually teach on the dangers of sense pleasures. Sense pleasure is what makes us fat, it is why women are abused, and why people drink too much. It leads to wars.

But here the Buddha distinguishes between sense pleasures and the pleasures that come from meditation, from tranquility and serenity:

I thought: ‘Why am I afraid of that pleasure that has nothing to do with sensual pleasures and unwholesome states?’ I thought: ‘I am not afraid of that pleasure since it has nothing to do with sensual pleasures and unwholesome states.' - [MN 36.31]

The Buddha then nurses himself back to health, because, as he says, “It is not easy to attain that pleasure with a body so excessively emaciated.” [MN 36.33] He leaves the secluded caves where he was living, walks down the mountain, and crosses the Niranjana River, which is dry outside of the monsoon season. Here he continues his quest, near to the village of Uruvela, where he can get alms. Ultimately, he has his breakthrough.

The Buddha’s description of the night of his Awakening is so poetic, that I think I will let him speak for himself:

Now when I had eaten solid food and regained my strength, then quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, I entered upon and abided in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought, with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion. But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

With the stilling of applied and sustained thought, I entered upon and abided in the second jhāna…With the fading away as well of rapture…I entered upon and abided in the third jhāna…With the abandoning of pleasure and pain…I entered upon and abided in the fourth jhāna…But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

When my concentrated mind was thus purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection, malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability, I directed it to knowledge of the recollection of past lives. I recollected my manifold past lives, that is, one birth, two births… Thus with their aspects and particulars I recollected my manifold past lives.

This was the first true knowledge attained by me in the first watch of the night. Ignorance was banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose, as happens in one who abides diligent, ardent, and resolute. But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

When my concentrated mind was thus purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection, malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability, I directed it to knowledge of the passing away and reappearance of beings… Thus with the divine eye, which is purified and surpasses the human, I saw beings passing away and reappearing, inferior and superior, fair and ugly, fortunate and unfortunate, and I understood how beings pass on according to their actions.

This was the second true knowledge attained by me in the middle watch of the night. Ignorance was banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose happens in one who abides diligent, ardent, and resolute. But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain.

When my concentrated mind was thus purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection, malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability, I directed it to knowledge of the destruction of the taints. I directly knew as it actually is: ‘This is suffering’;…‘This is the origin of suffering’;…‘This is the cessation of suffering’;…‘This is the way leading to the cessation of suffering’;…‘These are the taints’;…‘This is the origin of the taints’;…‘This is the cessation of the taints’;…‘This is the way leading to the cessation of the taints.’

When I knew and saw thus, my mind was liberated from the taint of sensual desire, from the taint of being, and from the taint of ignorance. When it was liberated there came the knowledge: ‘It is liberated.’ I directly knew: ‘Birth is destroyed, the holy life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no more coming to any state of being.’

This was the third true knowledge attained by me in the last watch of the night. Ignorance was banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose, as happens in one who abides diligent, ardent, and resolute. But such pleasant feeling that arose in me did not invade my mind and remain. - [MN 36.34-44]

(Note: The "taints" - (Pāli: Āsavas, Sanskrit: Āśrava) - are (1) sense desire, (2) craving for existence, and (3) ignorance.)

Thus, the Buddha started the night by attaining, in turn, the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th jhānas. These are states of deep concentration (meditative absorption). In the 4th jhāna his "concentrated mind was thus purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection, malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability". He had a sharp instrument with which to gain insight.

You may recognize from the first section of the meditation guide that we are following precisely the Buddha’s path. We have not gotten to jhāna – yet – but we are cultivating concentration and tranquility in the same way that the Buddha did.

What happens next is that the Buddha uses this "mind thus purified" to examine his previous lives. This may be a little hard for you to handle at this point, and if it is, don’t worry about it. Don’t turn it into a problem. But it is worth describing his Awakening in exactly the way the Buddha does. Rebirth is a fundamental part of the Buddha’s teaching. The whole of the Dharma hangs together in a uniquely coherent way. Many teachers teach only what they choose to believe, based on their cultural conditioning. But this path is about transcending our habits and conditioning. If rebirth is a problem for you, put it onto a back shelf in your mind for now, but also know that rebirth is a central part of the Buddha's teaching.

This happens in the "first watch of the night". In India they divided the night into three "watches", and each watch was four hours long.

On the second watch of the night the Buddha turned his attention to how beings are born and reborn "according to their actions". This last phrase is the key. How we behave determines our future.

This is a complicated topic, and one that we will cover in detail. However, for now, if you have led a very immoral life, don’t panic. There is a famous monk from the Buddha’s time who had been a serial killer. His name was Angulimala. He killed 999 people. And yet he attained a full Awakening. He became a Buddhist saint of sorts.

Karma is not deterministic. It is about the decisions that we make here and now. This training is about cultivating skillfulness, and through skillfulness we create a more wholesome life for ourselves now and in the future. And this has the inestimable value of being of great service to everyone around us. Those two things are tightly bound.

In the last watch of the night, the Buddha discovered the Four Noble Truths:

- The Noble Truth of suffering.

- The Noble Truth of the cause of suffering.

- The Noble Truth of the cessation of suffering.

- The Noble Truth of the path that leads to the end of suffering.

And with that we have some inkling of what the Buddha’s path was, how he got there, and what he learned. However, so far this is just the tip of the iceberg. In the next section we will go into more detail about the Four Noble Truths, and what the Buddha discovered in that third watch of the night.

Summary

In this chapter we examined the life of the Buddha, and how his life can be an archetype for our own spiritual journey.

The Buddha was born into a life of extreme luxury, but when he examined that life he found it wanting. No matter how much wealth, beauty, power and luxury he had, he would still be subject to old age, sickness, and death. Thus he left this life to see if he could find something better.

His first two teachers taught him the transcendent meditation attainments of the base of nothingness and the base of neither perception nor non-perception. He was so adept at these practice that his teachers offered him a place as their co-teacher. But the Buddha was not satisfied that this was all there is.

He then undertook great physical austerities to "burn off" his karma, as a way to end the cycle of life and birth. After nearly dying, he gave up on this, too, as a path to liberation.

Finally he remembered a time when he was a child - under a rose apple tree - when he entered the 1st jhāna, a state of meditative absorption. "Why should I be afraid of this pleasure born of seclusion", he thought. "Could this be the path to Awakening?"

He nursed himself back to health while cultivating these states of meditative absorption. This helped him develop a mind that was "thus purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection, malleable, wieldy, steady, and attained to imperturbability", a mind that enabled him to see into his previous lives, the law of karma, and finally the Four Noble Truths. He had attained an Awakening; he had become the Buddha.

Figure:

Rose-apple tree

Figure:

Rose-apple tree